ALL ROADS LEAD TO WEYMOUTH ...

‘Every aspect of the Weymouth Coast sank into my mind with such a transubstantiating magic [that] it is through the medium of these things that I envisage all the experiences of my life’

(Autobiography, John Cowper Powys 1967:151)

In just under three weeks' time I'll be making the first, tentative steps on my ‘I will walk five thousand miles’ endeavour. And when I’ve walked five thousand miles I will, of course, walk five thousand more. As the Rolling Stones once sang, ‘if you start me up, I’ll never stop. Never stop, never stop’. Over the course of the next couple of years I’ll be making personal pilgrimages to the places that have shaped my life because, as the title of my PhD thesis put it, I am the land, the land is me. It will always be thus, forever, until the day I die. Over the decades I’ve become part of the landscape through which I walk, we are inseparable and, increasingly, indistinguishable.

From the moment of this project’s inception, there was no doubt as where it would begin and, if it really must end, where it might come to a conclusion. To be clear, Weymouth wasn’t the start, for the first eighteen years of my life I was blissfully unaware of the Dorset seaside town’s existence, but it was the catalyst. No, more than that, it was my prime mover. Without Weymouth there’d be no Siân Lacey Taylder, or at least no Doctor Siân Lacey Taylder; it’s ironic that the cause of my middle-age success was the juvenile failure which took me to the lecture halls – or rather, student bar – of the Dorset Institute of Higher Education (DIHE) rather than the University of Stirling.

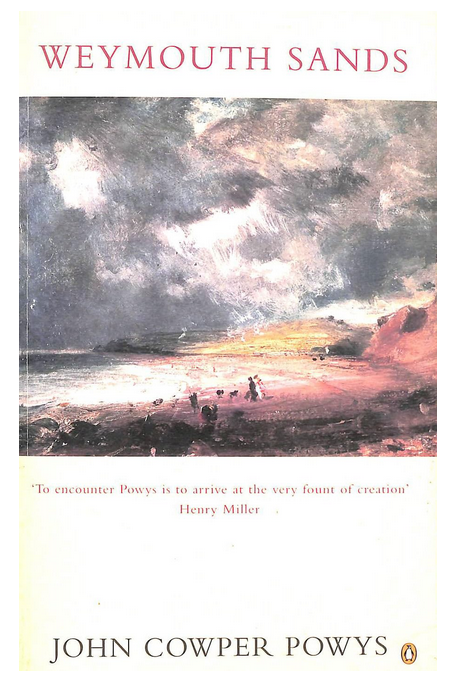

More of that when I walk into and around Weymouth next month, with my very special guest The Mucker. For the moment I want to pay homage to the author, one of the UK’s most underrated, who gave voice to my emotions long before I could. The third of John Cowper Powys’ four Wessex novels, Weymouth Sands was first published in the UK in 1935 as Jobber Skald. Having been successfully sued for libel in the second, A Glastonbury Romance, he was taking no chances and removed all references to real-life Weymouth and its inhabitants. It’s not hard to see why, Weymouth Sands is brim-full with a striking collection of eccentrics and oddities, as John Gray writes, in his Wessex suite, ‘Powys evokes the floating world of moment-to-moment awareness as found in a collection of characters living on the edges of society, struggling to fashion a life in which their contradictory impulses could somehow be reconciled’.

I first arrived in Weymouth, on the train from Waterloo, on a grey and cloudy afternoon in early October 1983. Having discovered sex, booze and rock ‘n’ roll during my A level years I’d cocked up my exams but secured a place at the DIHE to study Geography and Landscape Studies. That I somehow managed to squeeze a third was largely due to a creative approach to my dissertation on landscape and literature in post-Thomas Hardy Wessex. I fancied myself as a poet so, adopting a pseudonym (which I think was Sarah Rodden) and making up a non-existent self-published booklet, wrote about myself. Nothing new there! But the main focus of my dissertation, written in exile in Bournemouth, was John Cowper Powys and Weymouth Sands. Nearly forty years later I would adopt a ‘Powysian’ method to representing landscapes on the Camino de Santiago for my PhD thesis. I do love it when the world turns full circle.

‘It was an impression as if the whole of Weymouth had suddenly become an insubstantial vapour suspended in place. All the particular aspects of the place known to him so well, the spire of St John’s Church, the rounded, stucco-façade of Number One Brunswick Terrace and of Number One, St Mary’s Street, the Jubilee Clock, the Nothe, the statue of George the Third, seemed to emerge gigantically from a mass of vapourous unreality’.

Since the first publication of Weymouth Sands Powys has gone in and out of fashion but remains an acquired taste. As a landscape writer he is surely Hardy’s worthy successor, opening salvoes don’t come much better than this (reminding me, incidentally, of the first lines of The Return of the Native.

'The sea lost nothing of the swallowing identity of its great outer mass of waters in the emphatic, individual character of each particular wave. Each wave, as it rolled in upon the high-pebbled beach, was an epitome of the whole body of the sea, and carried with it all the vast mysterious quality of the earth’s ancient antagonist'.

But my personal engagement with Weymouth Sands went beyond the exquisite descriptions of the town, its landmarks repeated like a litany in the Roman Catholic mass to create to create a ‘sense of mysterious becoming’. I was eighteen years old, naïvely immature and desperately in search of a defining personality. It was against the backdrop of Weymouth that I began to develop, and not always in a good way. But, reading the novel once again, forty years later, I realise how much I ‘became’ in Weymouth, how much the town shaped me and left its imprint on my psyche and on my soul. It’s a ‘a strange, phantasmal Weymouth, a mystical town made of solemn sadness, gathered itself about him, a town built out of the smell of dead seaweed, a town whose very walls and roofs were composed of flying spindrift and tossing rain’. At the beginning of next month I’ll devote an entire day to exploring the streets of Weymouth and talk at greater length about Powys and the landscapes of my youth. But I’ll finish with these words, from one of the novels several protagonists, the tutor Magnus Muir:

'How well he knew this spot! It was one of those geographical points on the surface of the planet that would surely rush into his mind when he came to die, as a concentrated essence of all that life meant!'